Buried somewhere inside our library lies our leather-bound, turn-of-the20th-century (newly-updated with the latest black-and-white photographs!), edition of Mrs. Beeton’s Household Management. Our library presently rests in a (mostly) packed-up state. We grieve not having Mrs. Beeton to hand, as both I and the better half use the recipes. This is no mere cookbook, esteemed readers. It is an encyclopaedia on how to order your life and the lives of those who share your home. Mrs. Beeton provides all the information the mistress of the house will need when, as it inevitably does, the occasion arises for her to perform (some not-so minor) surgical procedures, draft a will, grow food, repair most anything, call on acquaintances, draw up accounts, or sell land.

Late Medieval English poetry did what Isabella Beeton did, 500 years earlier: law, politics, diet and cooking, you name it, there’s something written about it in verse by some medieval monk in a scriptorium. Like Mrs. Beeton, the monks knew of what they wrote. Although the poems perhaps seem to us somewhat naïve or unsophisticated, this is hardly the case.

Starting with the law, allow me a brief personal digression. I am a lawyer. I am presently the type of lawyer who wears a funny costume whose general, and traditional, task in working life is to go to court because a dispute has arisen. Putting crime and family matters aside, court cases happen when somebody, usually a lawyer, has messed up: breached a contract, acted negligently causing damage, got a property transaction wrong, or acted outside his/her/its lawful powers (in the case of the government or those who exercise government functions). For it not going wrong, which is the goal contrary to what starry-eyed law students who marvel at the decisions of the higher Courts might think, here in England there’s another branch of the legal profession, the solicitor. Buy a house, write a will, set up a trust, structure a gift / giving, use the law to save the tax man the trouble and expense of collecting any from you – this is the world of the solicitor who, if she is the perfect solicitor, never makes a mark on the legal world or the law itself (i.e. goes to appeal) unless the other side has messed up. The world of non-contentious law. I used to be one of those lawyers, so I know about it although never once ever practiced in a non-contentious area beyond advising people on how to apply for welfare benefits.

The following poem, until the Law of Property Act 1925, and associated acts, would have served as an 80 – 85% complete and 100% correct guide to the conveyancing (transfer) of real property (estate). Prior to the 1925 Act, no central registry for land title existed. Each property transaction had to involve the physical inspection of deeds and potentially many other documents. The institution of the Land Registry here in England & Wales has made much, but not all, of that process much easier now. Barclays Bank no longer has to physically write the details of your mortgage on the deeds to your (their) house which, at least until a decade or two ago, were still retained by the bank until the mortgage is redeemed in full. These properties still exist. The registration requirement gets triggered upon sale and a surprising percentage of this country (well above 15%) has not changed hands since 1925. As ever, the Middle English Glossary has been updated in the Reference & Guides:

Whoso wyll be were in purchasyng,

Consider the poyntys that be therinne:

Fyrst se that the lond be clere

In the tytell of the sellere,

And that it stond in no daunger

Of no womans dewere.

Se wher the lond be bound or fre,

And se the reles of every feffé.

Se that the seller be of age,

And whether it stond in any mortgage.

Loke whether a tayle thereof may be fonde,

And whether it stond in statute bounde.

Consyder what servys longys therto,

And what whyte-rente there oute must go.

And if it meve of a weddyd woman,

Luke ryght wele if that thou cane.

And if thou may in any wyse,

Make a charter of warantys

To thyn eyres and asygnés also.

Thus schall a wyse purchesor do;

And in ten yere if thou wyse be,

Thou schall ageyn thi money se.

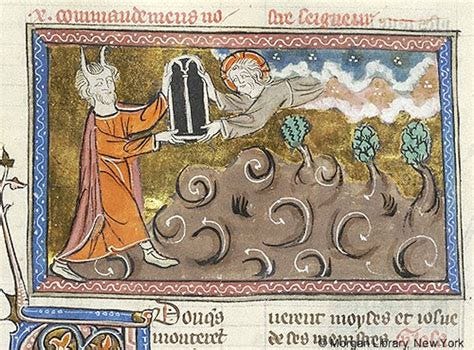

I shall not be as long-winded in introducing the last two poems. I do not like the idea of commenting too much on matters religious, as I am a most wretched sinner, and the other half tells me I am a mediocre cook. That being said, the poem on the Ten Commandments does not lack theological subtlety:

Herkyns, syrys, that standys abowte:

I wyll yow tell with gode entente,

How ye to God schuld knele and lowte,

If ye wyll kepe his commandment.

Thow schall loff God with herte entere,

With all thi sawle and all thi myght.

Other god in no maner

Thou schall not have be dey ne nyght.

Thy Godys name in vanyté

Thow schall not take, for welle ne woo;

Dismembyr hym not that on the rode tree

For thee was made full blake and bloo.

Thy holy deys kepe wele also;

Fro werldly werkys thou take thi reste.

All thy howsold the same schall do,

Bothe wyffe and chyld, servant and beste.

Thy fader and moder thou schall honour,

Not only with thi reverence:

In all ther nede be ther sokowre,

And kepe aye Goddys obedyence.

Of mans kynd thou schall not sley,

Ne herme with word ne wyll ne dede.

Ne no mans gode thou take awey,

If thou may helpe them at there nede.

Thy wyff thou mayste in tyme wele take,

Bot non other lawfully.

Lechery and synfull luste thou forsake,

And dred aye God wereever thou be.

Be thou no theffe ne theffys fere,

Ne nothyng wyne thorow trechery.

Ocure ne symony cum thou not nere,

Bot consciens clere kepe aye truly.

Thow schall in word be trewe also,

And wytnes fals schall thou non bere.

No lye thou make for frend ne foo,

Leste thou thy sawle full gretly dere.

Thi neyghbours wyff thou nought desyre,

Ne womane none throw synne covet;

Bot as Holy Chyrch wold it were,

Ryght so thi pourpos luke thou sette.

Howse ne lond ne other thing

Thow schall not covet wrongfully;

Bot kepe well aye Godys bydding,

And Crysten feyth leve stedfastly.

Thes be the commandmentys ten

That bene wryte in this scryptour,

That God gaff to Moysen

(Them to kepe, loke ye before)

In two tabullys of ston ryght

To helpe mans kynd forth of synne,

Wryten with the hond of God allmyght,

To teche mankynd this werld to wynne.

All thei that thes commandmentys kepe,

In heven with God schall ever wonne;

Yiff that they wyll fro syn them kepe,

They schall be bryghter than the sonne.

AMEN QUOD RATE.

Not eating meat on Fridays never seemed penitential to me as a child. That meant fish or pizza, both a treat. To this day I must make a concerted effort to skip breakfast, eat a late fish lunch and then go back to experiencing hunger after the sheer bliss of cod & chips or, say, halibut in a tarragon, shallot and butter sauce with boiled Cyprus potatoes, steamed zucchini and salad has subsided. Not eating meat and fasting on Friday both continue to delight me - public, if we eat together - Catholic. The following recipe, dearest readers, would likely count as a highly penitential meal, one which perhaps would smell publically for some distance:

For a servise on fysshe day.

Fyrst white pese and porray þou take,

Cover þy white heryng for goddys sake;

Þen cover red heryng and set abufe,

And mustard on heghe, for goddys lufe;

Þen cover salt salmon on hast,

Salt ele þer wyth on þis course last.

For þe secunde course, so god me glad,

Take ryse and fletande fignade,

Þan salt fysshe and stok fysshe take þou schalle,

For last of þis course, so fayre me falle.

For þe iii cours sowpys dorre fyne,

And also lampronus in galentyne,

Bakun turbut and sawmon ibake

Alle fresshe, and smalle fysshe þou take

Þer with, als trouȝte, sperlynges1. [the smelt.] and menwus with al,

And loches to hom sawce versance shal.

The weird letter which looks like an over ambitions “p” (þ) is “th” always. I like it and think we ought to have kept that one rather than have “th.”

Yours in orthography,

Peregrinus

These are wonderful! I am amazed at the property one. I vaguely remember my property law and the archaic terms used, but seeing them written down so long ago is a treat. And what a great way to remember the ten commandments!

Mahalo