Catholic London: where to start?

All Hallowes Tower Hill: Romans, Americans, Crusaders

At that moment every thing seemed to combine to make my prospects brilliant – My father had entered into the most favorable arrangements with his creditors . . . We became acquainted with Mr. T[homas] B[oylston] A[dams] - who accompanied his brother who soon won the hearts of all the family. On the Wednesday 26 July 1797 I became a bride under as every body thought the happiest of auspices – I must here observe that my mother expressed her surprize at my having fixed so early a day and rebuked me for not having consulted her; and I felt ashamed at the idea of being thought so indelicate the more so as it seemed to me upon reflection that Mr. A appeared surprized also . . .1

So wrote Louisa Catherine Adams, the wife of John Quincy, of her nuptials at All Hallowes. John Quincy became about as excited as he ever got in his diary entry for the day:

At nine this morning I went accompanied by my brother to Mr: Johnson’s, and thence to the Church of the Parish of All Hallows, Barking, where I was married to Louisa Catherine Johnson, the second Daughter of Joshua and Catherine Johnson,—by Mr: Hewlett— Mr: Johnson’s family, Mr: Brooks, my brother and Mr: J. Hall were present. We were married before 11. in the morning: And immediately after, went out to see Tilney House; one of the splendid Country seats for which this Country is distinguished.— We returned at about 4. P.M. The company before mentioned, and Mrs: Court a friend of Mrs: Johnson, dined with us.— The day was a very long one and closed at about 11.2

All Hallowes, Barking as was, Tower Hill as is now, may very well pre-date the Norman Conquest as a place of Catholic worship. The abbey of Barking – which was located in what are now the Barking and East Ham areas of east London – certainly existed before the Conquest. It is possible that the abbey’s possessions as listed in the Domesday Book, including a church in London proper, included All Hallowes.

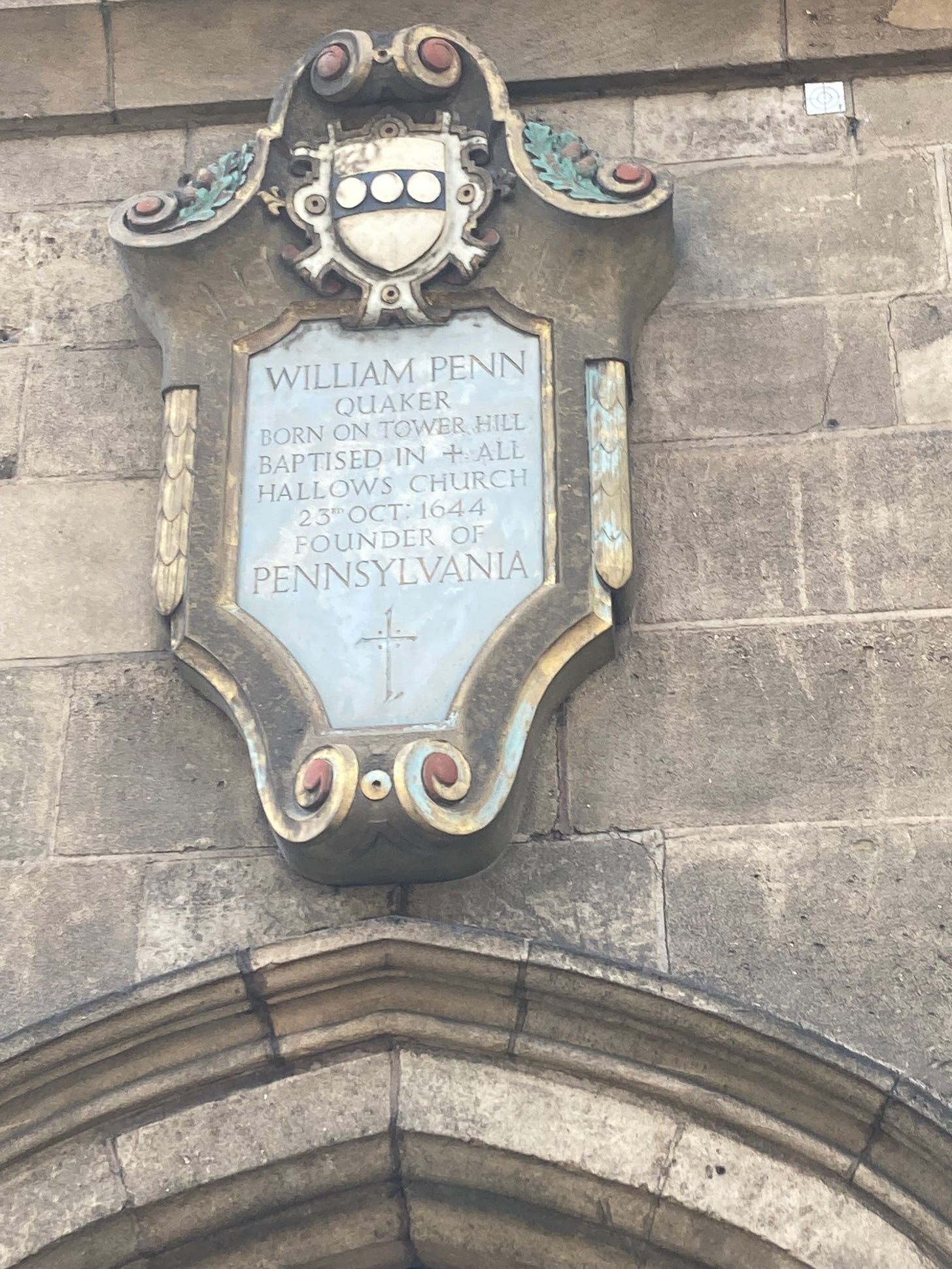

One hundred and thirty five years prior to the marriage of Louisa and John Quincy Adams, All Hallowes saw the baptism of the man who invented Pennsylvania:

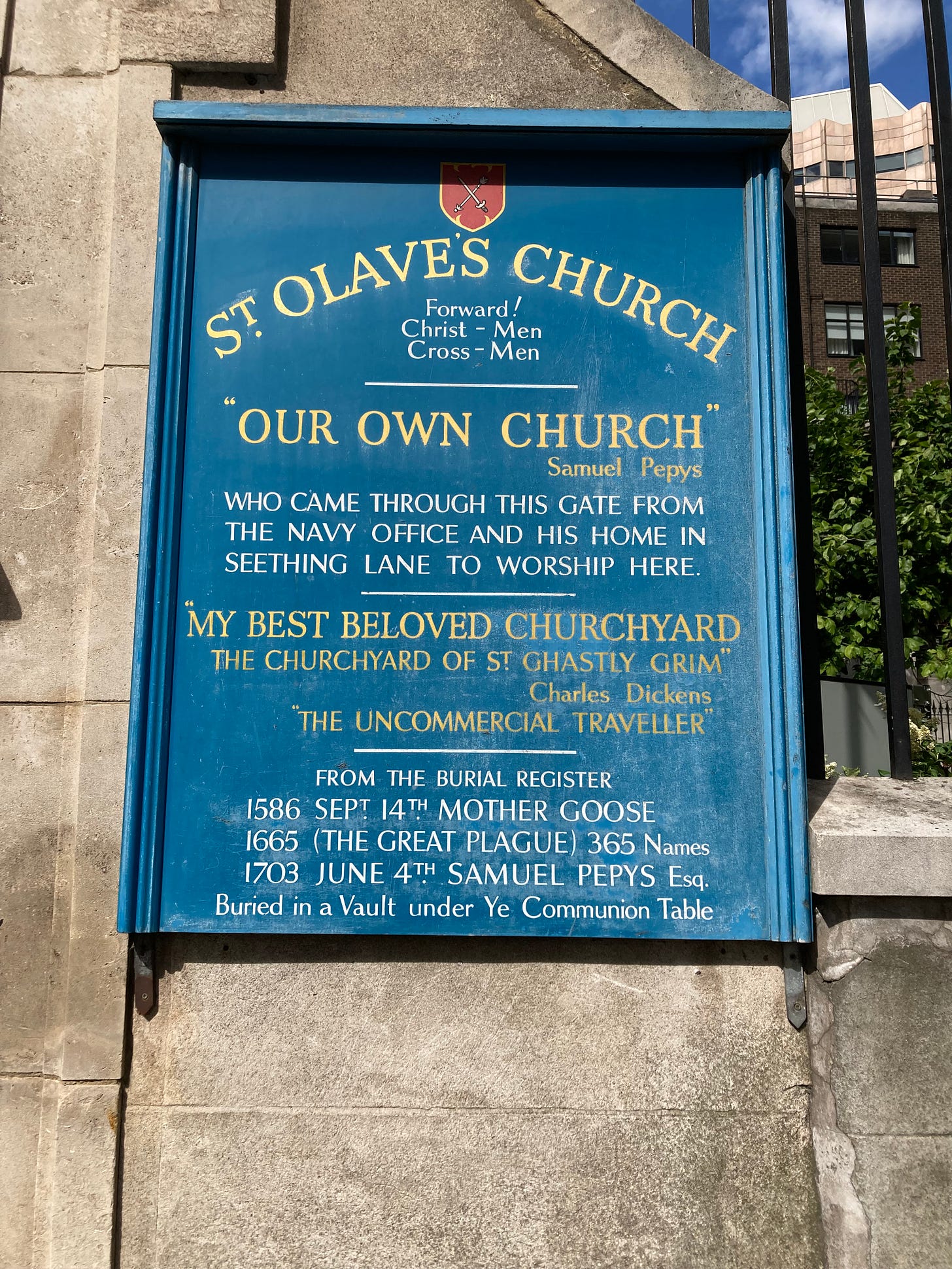

This church has survived. It survived the Great Fire which means it remains one of the few Churches in the City of London which Christopher Wren did not rebuild or replace. Samuel Pepys watched said Great Fire from the spire while William Penn rushed over to the sister parish of St. Olave's to save it from the flames by helpfully blowing up all the surrounding buildings to create a fire-break. St. Olave's Church has other claims to fame:

Returning to All Hallowes, I will not provide extensive photographs in this screed. The Church itself has a very helpful website, albeit perhaps somewhat over-optimistic estimation of the antiquity of certain bits, and parts of it are a museum.3 The lower regions constitute a museum and I have an editorial policy not to risk reducing attendance at said museum (it’s free of cost, but provides guided tours) or creating a rival website. I shall resort to London’s other great (greatest?) asset, her libraries.

John Stow,4 in his 1598 Survey of London, wrote this about All Hallowes:

Now therefore, to begin at the east end of the street [Tower Street], ono the north side thereof, is the fair parish church called All Hallows Barking, which standeth in a large, but sometime far larger, cemetery or churchyard; on the north side whereof was sometime build a fair chapel, founded by King Richard I; some have written that his heart was buried there under the high altar. This chapel was confirmed and augmented by King Edward I. . . . The chapel and college were suppressed and pulled down in the year 1548, the 2nd of King Edward VI. The ground was employed as a garden-plot furing the reigns of King Edward, Queen Mary, and part of Queen Elizabeth, until at length a large strong frame of timber and brick was set thereon, and employed as a store-house of merchants’ goods brought from the sea by Sir William Winter, etc.5

All Hallowes, like many others, got mauled in the last series of arial bombardments. A fair amount of the 15th century walls survived, in part or in whole, or were expertly reconstructed after the war – a completion which took until 1957 to complete. During the war, archaeology from above revealed the presence of what appeared to be an Anglo-Saxon arch, constructed in part of Roman bricks which were laying around at the time. Estimates of the time construction vary from very early (7th century) to just before the Norman Conquest:

These are just the highlights of the upstairs portion of All Hallowes. In the 1920s, someone had occasion to do some digging underneath the church whereupon a number of interesting artifacts and structures came to light: 2nd century Roman pavements and grave markers, Anglo-Saxon crosses and sculpture, and three chapels. As mentioned above, I do not wish to set up a rival website and this part is a museum, so I shall limit my photos to these two, the first a shot looking down the length of the church facing east, that is toward the main altar upstairs:

At the end of this photograph we discover this chapel altar:

That, dear readers, is by some accounts the altar from the chapel of Richard I, Coeur de Leon, at Altit Castle in the Holy Land.6 The chapel itself is backed by 14th century walls. The Knights Templar built the castle at Altit in the 13th century during the 5th Crusade. It would appear that the writers to whom John Stow referred in 1598 were on to something.7 It would also seem that All Hallowes played a role in hosting the final undoing of the Templars in England. When the London Templars finally fell to be examined, at first without the use of torture and then with it due to pressure from Rome, this occurred at the Tower initially but then occurred at various churches around the City as the inquisitors began to isolate the Templars from one another in order to effect more fruitful enquiries. From the parish website, I get the impression that this may have occurred at All Hallowes, either in a former chapel of St. Mary on the site or at a sister parish at the time.

That, dear readers, brings this screed to a close. When next venturing out and about in Catholic London, I shall venture west along the Thames to just beyond the end of the City of London, as was in the 14th and 15th century.

Peregrinus

Hogan & Taylor, p. 31; it would appear that Mrs. Adams may be being a bit coy here. Those favorable arrangements her father had made fell apart two days after the wedding, thereby depriving the newlyweds of the promised marriage settlement. It turns out, Louisa’s father, Mr. Johnson, was a bit of a shady character.

From one of the National Archive or academic online collections of John Quincy Adams’s writings.

The ground floor is not a museum.

Born about 1525, the son of a London Chandler. Became a tailor; free-man of the Merchant Taylors Company, 1547. Charged with complicity in Papal matters, 1568 – 70, but acquitted. Died 6th April 1605. From all accounts an autodidact.

Stow, p. 119.

Altit is located on the coast of Israel, just south of Haifa, at the foot of Mount Carmel. The castle itself continued to have a colorful history under the subsequent rulers of the Holy Land. During the British Mandate, the castle saw use as a detention center for illegal immigrants. That area of the coast has for sometime been part of a naval base.

This reminds me of another similar, and more charming, story. Legend has it that the House of the Virgin at Lareto in Italy was flown to its present location by Angels. It turns out, and this is confirmed by contemporary documentation, when the Crusader states were finally getting overrun, members of the Byzantine aristocratic family the Angeli took the opportunity to take the Virgin’s house with them on the way out.

That's a lovely saxon arch! Most interesting piece, thanks.

That altar!